US Corn, Soybean Production Could Drop by Half as the Earth Heats Up

July 24, 2019 by Paul AusickWhile it’s not too difficult to list the predicted effects of a warming global climate, putting those effects into an ordered list from most to least severe may be harder. Rising temperatures are forecast to increase the probability of drought, and a rising sea level threatens to displace millions of people. There is also the question of the food supply.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service has released a report on the impact of climate change on federal programs that provide assistance to farmers to help them respond to production and market conditions. These programs include crop insurance, risk coverage and price loss coverage, among others, and have averaged costs of around $12 billion annually over the past decade, although fluctuations are “heavily influenced by weather variability.”

Thus, the Economic Research Service study sought to analyze the direct impact of climate on yield risk, the indirect effect of yield risk on price risk and the impact of changes in yield, price and production on the government’s total liabilities under the various insurance programs. While we may think that yield would drive the government’s costs higher as the climate gets warmer, what drives those costs higher are changes in the value of total crop production.

The report puts it this way: “Given that demand for most agricultural commodities is relatively inelastic, a decrease in total production would increase prices. Under these circumstances—the change in the quantity demanded is less than the change in price—prices increase proportionately more than the supply decreases.” The total value of the crop rises and the part of the crop covered by federal crop insurance becomes more valuable and raises government liabilities.

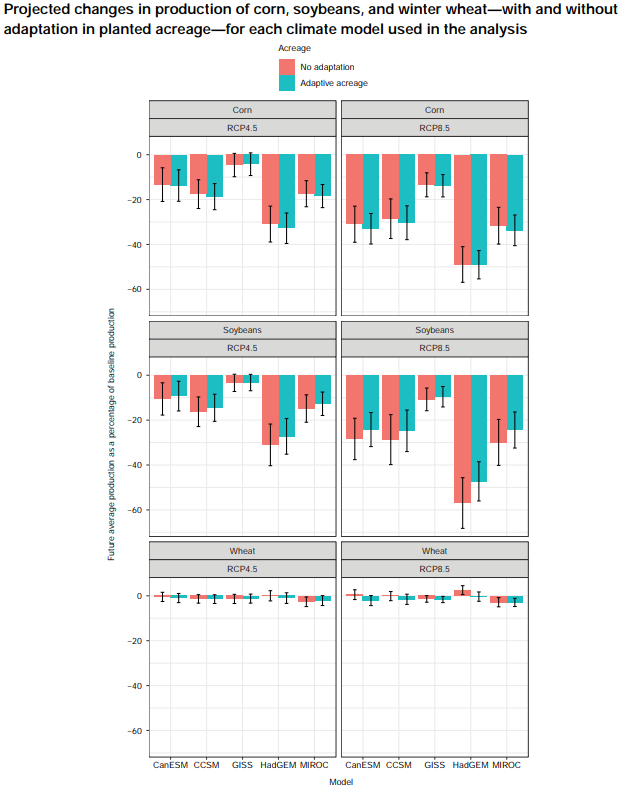

The report is based on five climate models with five different emissions scenarios called “representative concentration pathways,” or RCPs, that represent possible future emissions pathways to 2100. RCP4.5 represents a climate future in which “some amount of climate change mitigation occurs” and RCP8.5 represents a future “in which no mitigation occurs.” The crops reviewed in the report are corn, wheat and soybeans.

The following chart from the report shows the loss of production under both RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 for corn, soybeans and wheat in 2080. The orange bars indicate losses if acreage locations are not moved and methods of production are not changed. The blue bars indicate acreage that has been shifted to respond to new expected yields. Corn production drops nearly 50% by 2080 and soybean production drops by nearly 60% if no adaptation is allowed and nearly 50% if adaptation is allowed.

Overall, the climate models project declining average yields in corn and soybeans, while changes to winter wheat yields are modest and variable. Losses are generally largest in the southern United States and in dryland (non-irrigated) production. Yield changes in irrigated production generally are smaller than in dryland production.

The study did not try to assess the availability of irrigation water, even in areas that are currently irrigated. It does not seem unreasonable to think that a hotter climate will reduce the availability of water for irrigation.

Mark Twain once commented that whiskey’s for drinking and water’s for fighting over. That’s more or less always been true in the arid American West. Soon it may be true everywhere.