In March of 2010, drilling for oil went horizontal. Until then, vertical and directional (wellbores that bend up to 80 degrees) drilling made up more than half of U.S. rigs in operation. As of last Friday, horizontal rigs accounted for 87.4% of all drilling in the United States.

Actions have consequences and one consequence of the decade-long focus on horizontal drilling is that discoveries of new conventional oil and gas plays have reached a 70-year low, according to a new report from IHS Markit. The move to unconventional drilling has “far-reaching implications that could limit future conventional reserves additions,” the report notes.

Horizontal drilling (and fracking) have dominated not only because of low crude oil prices but also by the short cycle-times for unconventional projects and demands from investors who are no longer willing to front the money for long-term, high-cost projects.

Keith King, a senior advisor at IHS and lead author of the firm’s new report commented:

One of the main drivers here is the shift of investment by U.S. independents from international exploration to shale opportunities in the United States—shorter cycle-time projects—with greater flexibility to respond to changing market conditions. These operators can quickly turn an unconventional project off and stop or postpone drilling next month if oil prices fall.

Another factor chilling exploration and production in conventional fields is the maturity of the basin being explored. The average size of a conventional discovery varies widely based on the age of the basin. In early life-cycle basins, the average discovery size is 210 million barrels, compared to discoveries of just 25 million barrels in mature basins.

IHS Markit’s analysis also revealed that average discovery sizes in deep- and ultra-deep-water are five or more times larger than shallow water and onshore discoveries. That would seem to indicate that more drilling ought to take place in the areas where larger plays are likely to be found.

Instead, drillers are drilling fewer wells in these locations: “In 2014, 161 new field wildcats (NFW, exploratory oil wells drilled in unproven fields) were drilled in deep- and ultra-deep-water; by 2018 that number dropped to 68 wells. Drilling in frontier/emerging-phase basins declined by a similar amount.”

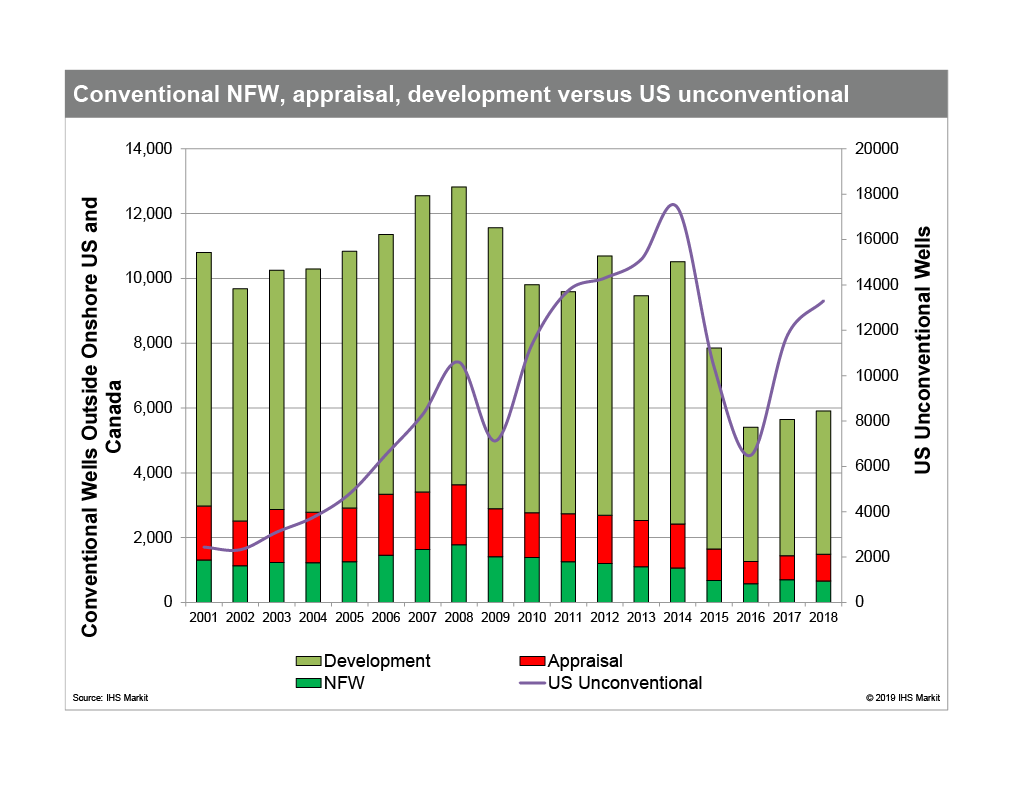

The following chart from IHS Markit shows, for example, that in 2018, more than 13,000 unconventional wells were drilled, compared to fewer than 6,000 conventional wells.

Despite recent large deepwater discoveries such as Exxon’s estimated find offshore of Guyana that now totals more than 6 billion barrels of estimated recoverable hydrocarbon resources, the trend is toward more unconventional drilling by the industry as a whole.

Still, IHS Markit’s King thinks there is a chance that the trend can be reversed:

Lackluster financial returns from unconventional production onshore in North America may drive more operators back to conventional exploration in the longer-term. Offshore companies have been able to substantially reduce the costs of building and operating offshore facilities necessary to develop resources in deeper waters. This renewed competitiveness could rekindle interest in conventional exploration where larger discoveries are made.

Horizontal drilling reaches peak well production much more quickly than vertical drilling, usually in less than a year from the time the well is completed. Production tails off nearly as quickly, although the well could continue to produce small quantities of oil for several years.

A conventional vertical well takes longer to reach its peak rate but production more or less plateaus at that rate for several years and using enhanced recovery techniques like water or carbon dioxide flooding can keep a well producing at higher rates much longer.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.