In March, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released its interim global economic outlook through 2020. The forecast for the United States called for the economy to rise by 2.6% this year and 2.2% next year. The forecast for Mexico called for growth of 2.0% this year and 2.3% in 2020.

In nominal dollars, Mexico’s gross domestic product, the world’s 15th largest, is expected to be about a 20th ($1.243 trillion) the size of U.S. GDP ($21.482 trillion) in 2019. Although Mexico’s economy is growing faster, the pace of growth would need to nearly double to push the country into the ranks of the world’s top 10 economies in five years.

That’s unlikely to happen. In its Economic Survey of Mexico published Thursday, the OECD lowered its estimate of Mexico’s economic growth for 2019 to 1.6% and its estimate for 2020 to 2.0%, largely due to a slowdown in the global economy and trade tensions that are disrupting — and may continue to disrupt — exports, private sector investment and global value chains.

According to the OECD, improving Mexico’s institutional quality would provide the most growth benefits of all the agency’s proposed structural reforms, having an impact on every other reform recommended in the report. Mexico’s anti-corruption initiatives are a good start but need to be expanded by creating an independent anti-corruption agency at the federal level. New competition enforcers and economic sectoral regulators also would help.

Among the country’s strengths are the macroeconomic framework that has driven strong export growth while at the same time lifting wages, remittances (cash sent to Mexican citizens from abroad) and consumer credit growth. The OECD suggests that investment in infrastructure projects, increasing domestic consumption and exports will continue to support the Mexican economy but at a slower pace of growth.

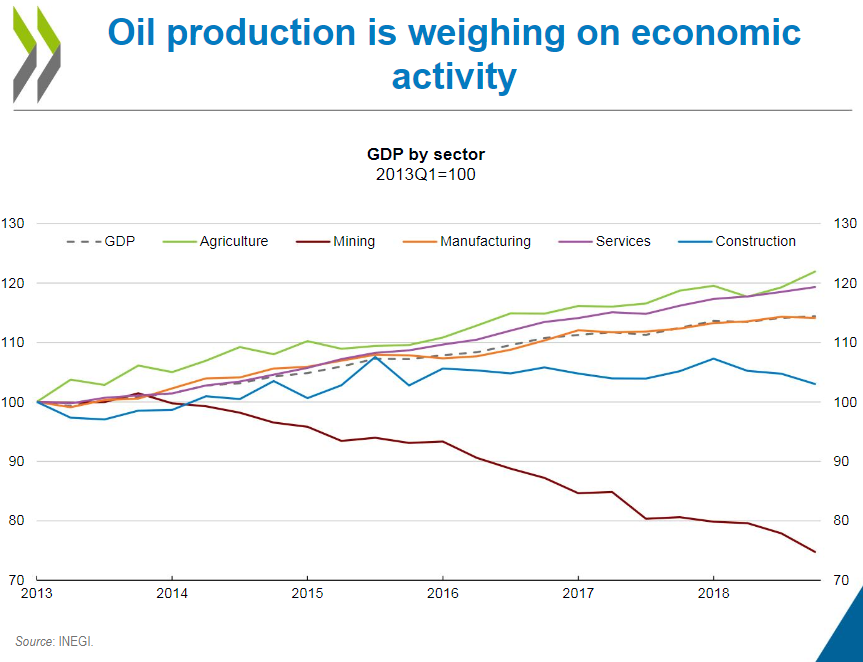

The bad news is that the country’s oil production has declined, constraining economic growth and reducing government revenues. The oil industry needs significant investment, primarily from foreign sources, but the outlook for new investment is “subdued, reflecting policy uncertainty domestically as well as abroad, but also fiscal consolidation, which has helped to halt the rise in public debt against a generally weak redistributive role of fiscal policy.”

Source: OECD

Tax revenue as a percentage of Mexico’s GDP is about half the OECD average of around 34%. Low tax collections limit what the country can spend on social services and infrastructure improvements. The OECD suggests raising the tax-to-GDP ratio “by broadening the tax base, and continuing to fight tax evasion and avoidance, including by reinforcing federal and state-level tax administrations.”

What the OECD calls “informality” is a reference to a labor market that does not offer workers some or all the usual legal protections that come with being a “formal” employee. Mexico’s high level of informality lowers productivity growth at the same time as it prevents the government from offering public benefits and enough tax receipts to pay for those redistributive benefits.

OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurria warned that Mexico currently faces headwinds internationally as well as internal structural challenges: “The only response is to continue designing and implementing new reforms to instill confidence, improve the quality of public administration, increase opportunities, reduce inequalities and bring about a stronger and more inclusive society for all Mexicans.”

A cynic might say that the Gurria’s observation could be applied to virtually any country. For the word “Mexicans” in his comment, substitute “Brazilians” or “Chinese” or “Americans.” Easy to say, hard to achieve.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.