By Joseph Kane, senior research associate and associate fellow at the Metropolitan Policy Program of the Brookings Institution

In the race to grow their economies and create new jobs, localities frequently look far beyond their borders. Too often, they try to lure new firms through costly incentives and subsidies with questionable economic returns, a trend that is only gaining more national spotlight during the search for Amazon’s second headquarters. But looking closer to home in support of their core industries and employment opportunities could more directly build off localities’ existing economic strengths.

Investing in infrastructure is foundational to these efforts. Not only does infrastructure serve as a platform to support industries and broader regional growth, but it can also be a driver of more equitable and enduring growth for individuals.

After all, constructing and maintaining reliable roads, ports, pipes, and other systems is essential to all types of businesses and households. Whether moving passengers and goods or ensuring that water, electricity, and broadband is available to everyone, both the public and private sector have a shared responsibility to oversee these various systems. Yet even beyond this supportive role, many local leaders overlook another significant opportunity: Infrastructure can also represent a key economic anchor.

For instance, the major facilities that utilities and transit agencies oversee serve as major public assets, but they also carry out many public responsibilities in their local communities—while employing millions of workers—which should warrant additional attention and investment. Since many of these jobs require less formal education and equip workers with applied experience and in-demand skills, they offer accessible, durable career growth in every community across the country. Think about all the jobs in water treatment plants, power plants, seaports, airports, and other infrastructure establishments nationally, found in large cities and rural areas alike.

As our recent report on the U.S. water infrastructure workforce shows, water utilities embody these anchor-like roles. They act as a key hub for jobs, training, and environmental stewardship at a local and regional level. On the lookout for a new generation of workers to construct, operate, and maintain pipes, plants, and numerous other water systems, utilities offer long-term, well-paid positions for workers across all skill levels. And the fact that they do so in some of the most disadvantaged areas nationally speaks to their unique role in expanding economic opportunity in their backyard.

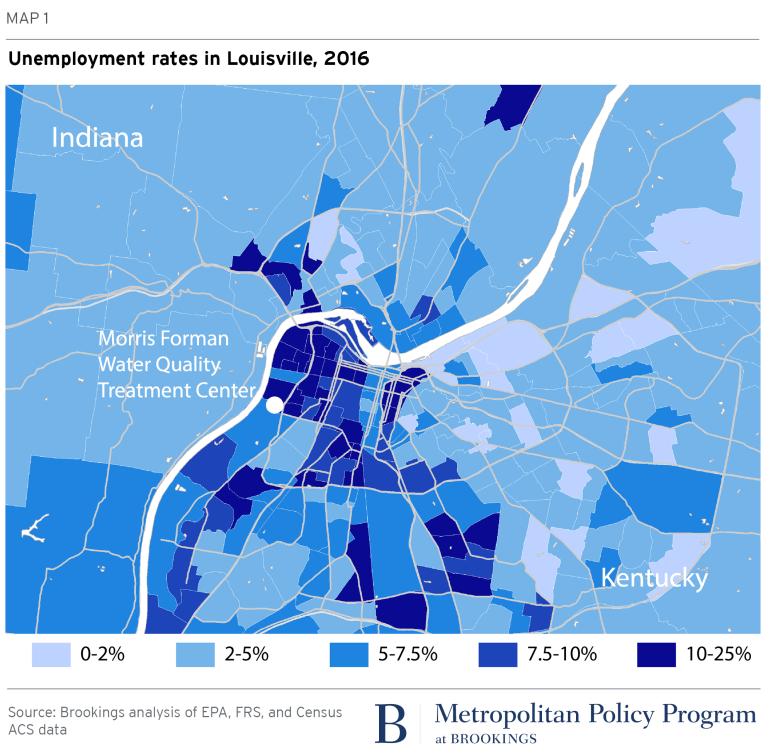

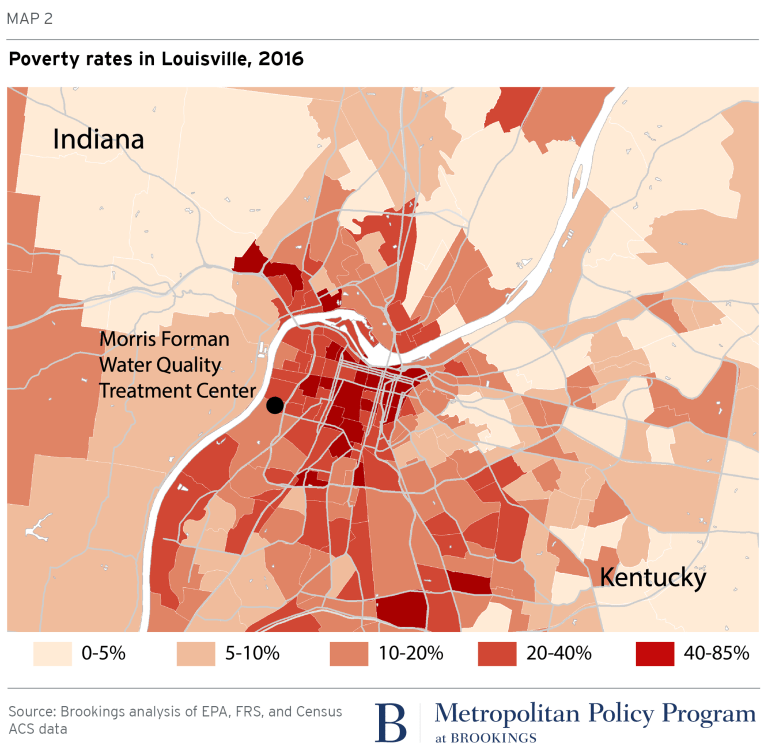

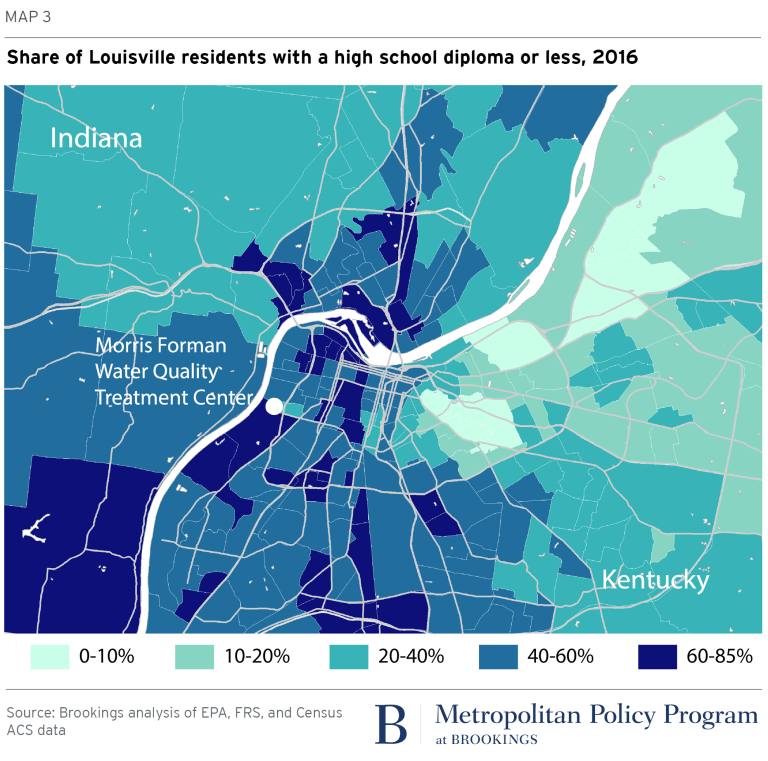

Looking at the locations of the country’s publicly owned water treatment plants—alongside the characteristics of the neighboring populations served—sheds more light on this dynamic. By analyzing spatial data from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Facility Registry Service and the American Community Survey, it is possible to see how demographics, educational attainment, unemployment, and poverty rates vary in tracts with water treatment plants.[i] Although these characteristics can differ markedly from place to place, one takeaway becomes clear: Many utilities concentrate operations in areas where residents experience higher unemployment and higher poverty.[ii]

As just one example, consider Louisville, Ky., which is aiming to improve its water infrastructure and connect local residents with careers in this space. Overseen by the Louisville and Jefferson County Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD), the Morris Forman Water Quality Treatment Center is the state’s largest water treatment plant, squarely located in an area where residents face significant economic shortfalls. In 2016, the unemployment rate stood at almost 10 percent for nearby workers, and the poverty rate stood at 29 percent—more than double the 4.5 percent unemployment rate and 14 percent poverty rate seen nationally. Furthermore, 54 percent of nearby workers only had a high school diploma or less, compared to 32.5 percent of all workers nationally.

In other words, at a time when utilities are looking to drive additional infrastructure improvements and hire more workers, there are many potential candidates looking for work who could fill these positions, essentially waiting at the door.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.