Oct. 30 marks the 80th anniversary of “The War of the Worlds” broadcast, the most famous, or infamous, program in radio history. Listeners who tuned in to the program late and did not hear the disclaimer that it was a radio play panicked thinking Martians had landed on Earth.

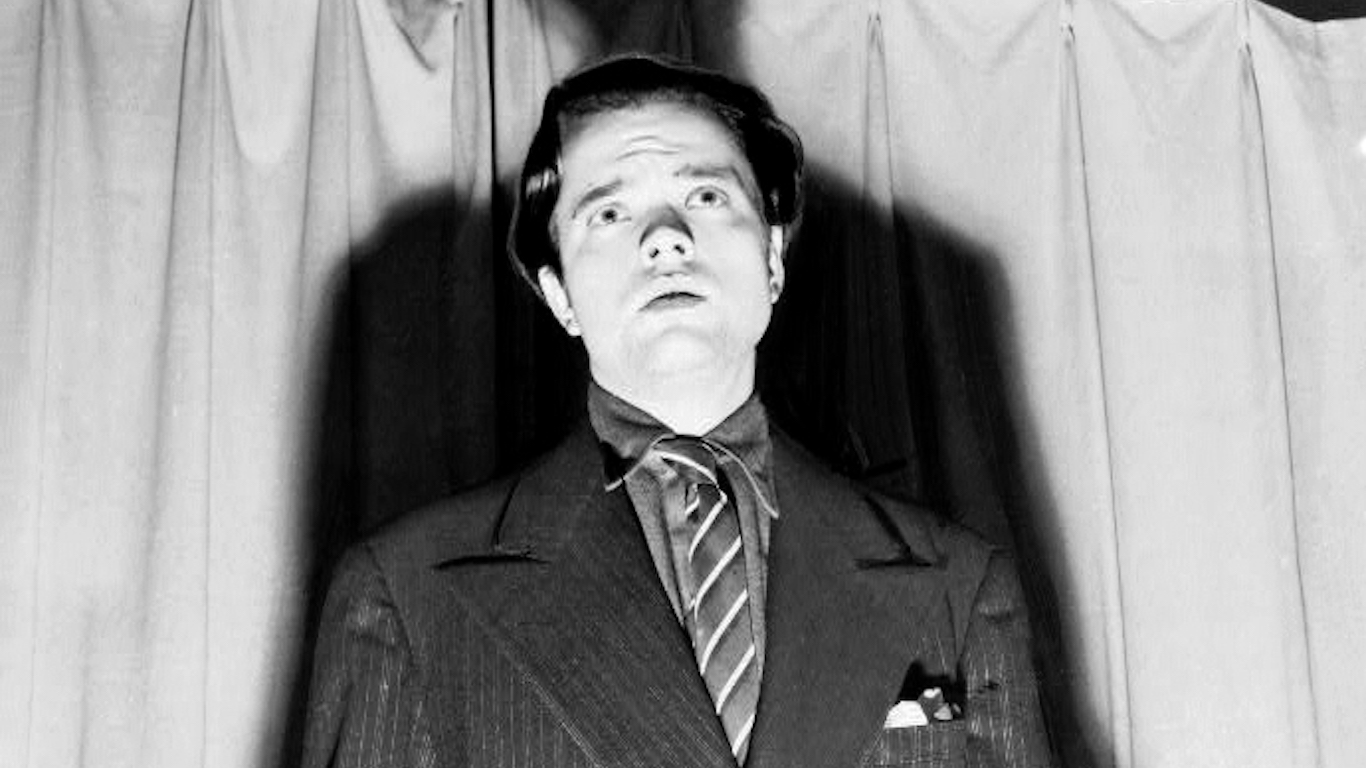

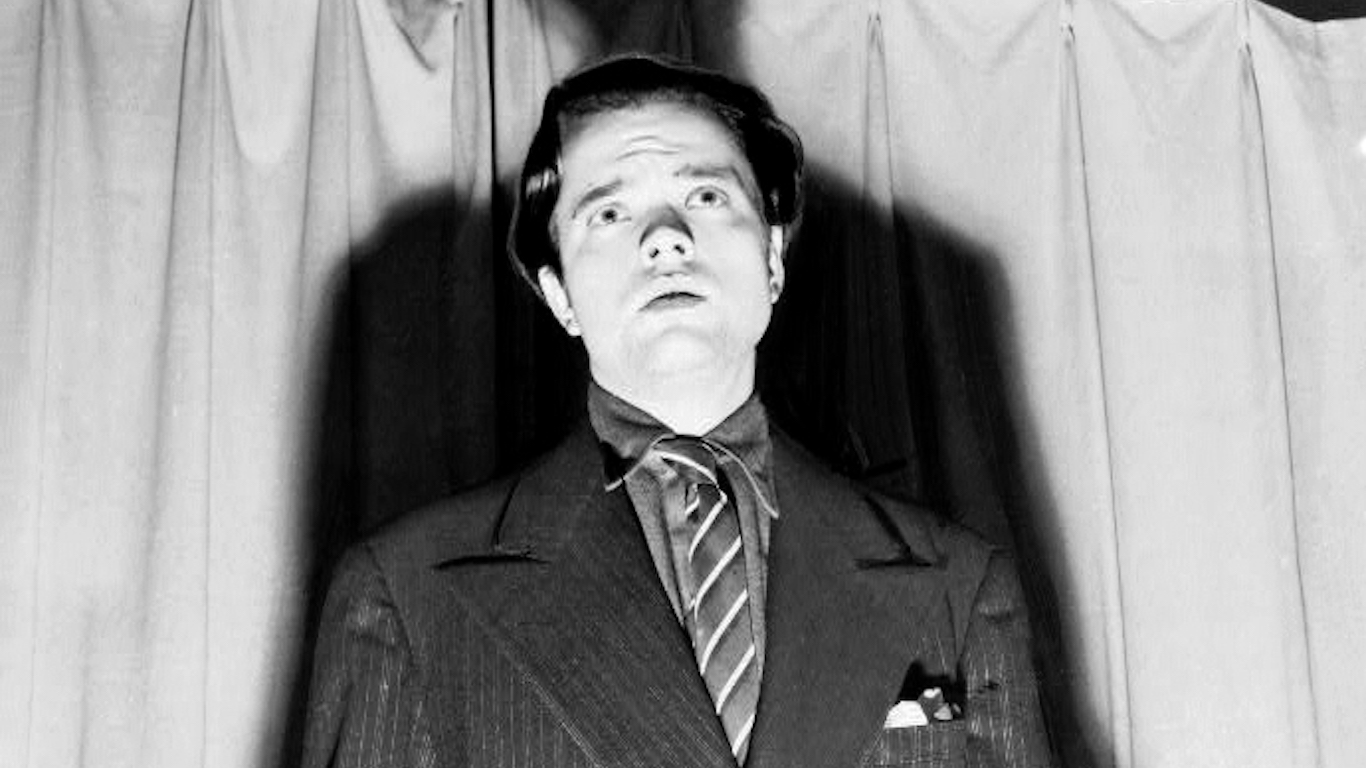

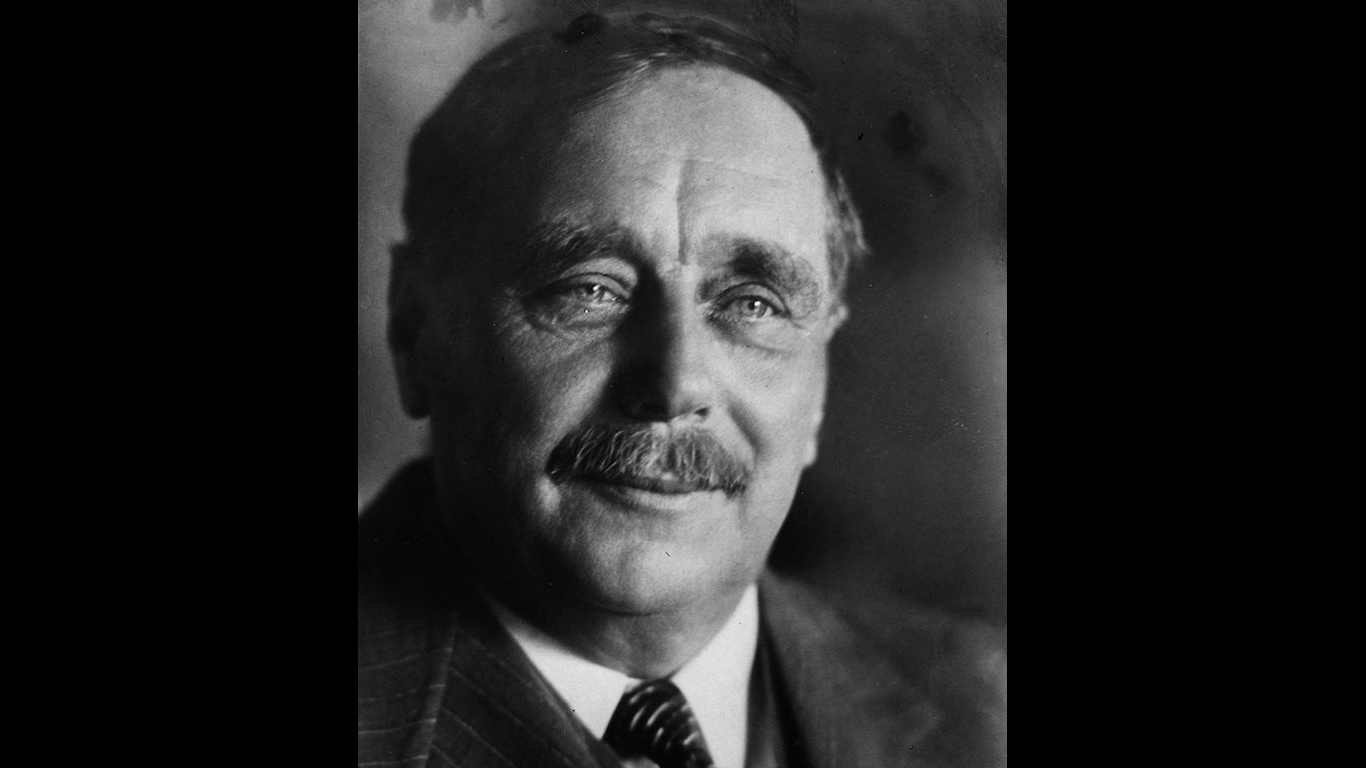

The ensuing furor made a celebrity of 23-year-old Orson Welles, who helmed the Mercury Theatre on the Air’s radio adaptation of the celebrated science fiction novel written by H.G. Wells. But the broadcast also raised concerns about Americans’ susceptibility to believe what has become known as “fake news” as well as issues about the responsibility of the media.

To mark the anniversary of the broadcast, 24/7 Wall St. has compiled a list of the 25 facts you need to know about “The War of the Worlds” broadcast. We created our list based on resource materials, audio clips from the broadcast as well as from other radio programs, podcasts, newspaper accounts of the program, and books on the subject.

Click here to see the 25 facts you need to know about “The War of the Worlds” broadcast.

Click here to read our detailed findings.

1. Anxious era

The broadcast tapped into the anxiety of the time. Just ahead of World War II, much of the world was nearly — or already — at war when the program aired. The Munich summit — at which Western powers allowed Germany to take over German-speaking parts of Czechoslovakia — had concluded a month before, and the tension was still palpable. Japan, controlled by militarists, was plundering China. And fascist Italy had overrun Ethiopia.

[in-text-ad]

2. Battle for customers

Radio and newspapers were slugging it out for market share throughout the 1930s. They had plenty of news fodder, including stories on the Lindbergh baby kidnapping and the Hindenburg disaster. Schwartz said that by 1938, radio and the print media had reached a detente, particularly by the time of the Munich diplomatic crisis a month earlier. “Newspapers had started affiliating with radio stations,” he said. “They realized they couldn’t outrun this new competitor, so they figured if you can’t beat them, join them. If you read the editorials after the broadcast, they are more critical of the listeners than radio.”

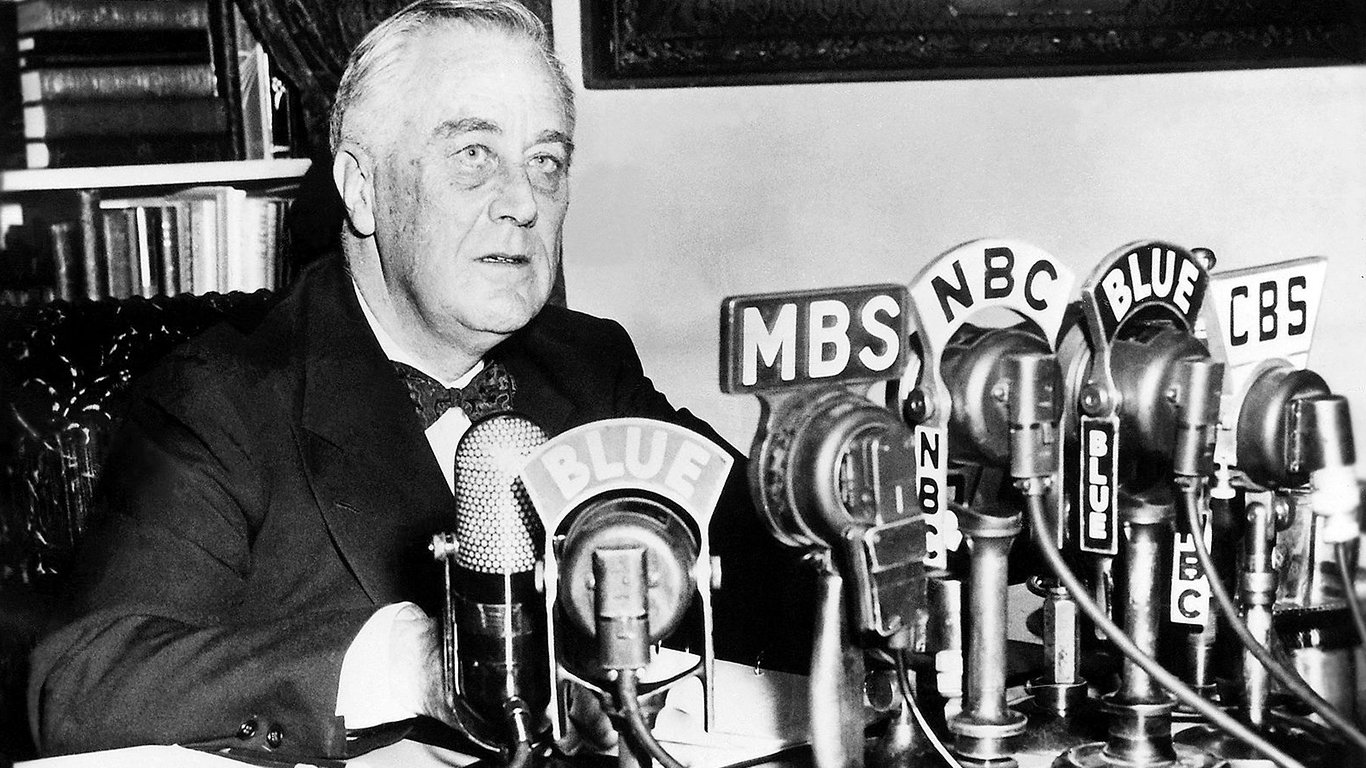

3. FDR’s stamp of approval

By 1938, radio had created for itself an aura of authority. President Franklin Roosevelt was using the medium for his “Fireside Chats,” in which he would talk to the American people about the issues of the day. Roosevelt recognized the power of the medium to engage the listener. “People treated those ‘Fireside Chats’ as a visit from the president into their living room,” said Schwartz. “They perceived this as a direct personal relationship with the president.”

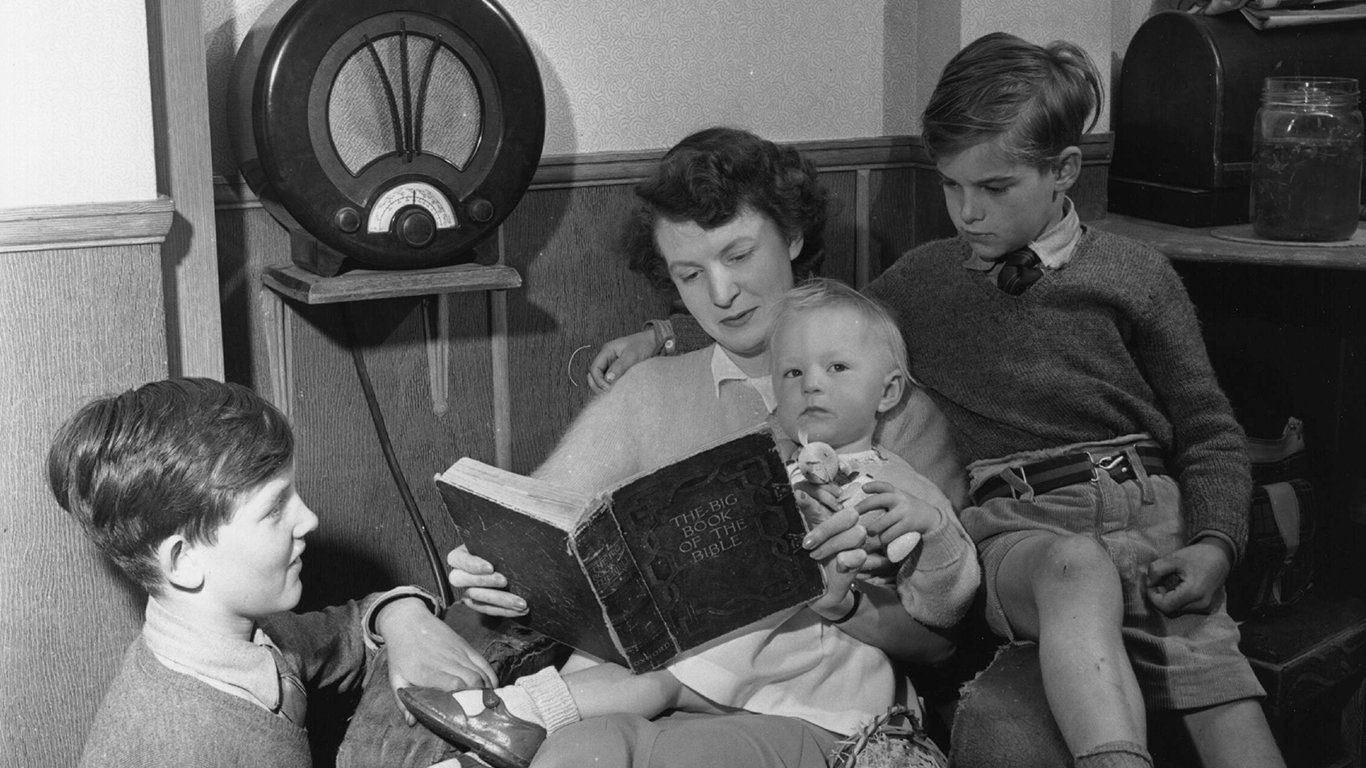

4. A radio in every home

In 1935, there were twice as many radios in American households as telephones. By 1939, there were 63,794 radio stations operating in the United States, broadcasting to about 27 million families who owned radio sets.

[in-text-ad-2]

5. A novel Idea

Mercury Theatre on the Air had performed works such as “Treasure Island” and “A Tale of Two Cities” and would have considered science fiction kind of lowbrow. “There was not a lot of faith in the show succeeding,” said Schwartz. “That moved people involved with the show to try to make the show as frightening and realistic as possible. They succeeded better than they ever expected.”

6. The landing spot

As writer Howard Koch was working on the script, it occurred to him that the story was going to include a pitched battle between Martians and the people of Earth. While traveling through New Jersey, he stopped at a gasoline station and bought a map. When he got home in Manhattan, he laid out the map, closed his eyes, and placed his pencil where the battle would take place — Grover’s Mill in central New Jersey.

[in-text-ad]

7. Why New Jersey?

Schwartz believes New Jersey was “invaded” because that part of the country was where a great deal of the population and media were at that time. “So much of the show centered in and around New York City, and New Jersey was the outlying place for that,” he said. “That’s why the Hindenburg was landing where it was (Lakehurst, New Jersey) — because that was the closest airstrip to New York City.”

8. Concerns about panic

Fearing the possibility of panic,The Mercury Theatre on the Air troupe began the program with a statement that said the following program was fiction. The disclaimer was repeated at the 40- and 55-minute mark of the program, and at the end of the broadcast. Even so, the radio station was flooded with phone calls during and after the broadcast.

9. Heightened tension

There was no commercial interruption during the broadcast, adding to the authenticity of breaking news. There was no commercial interruption because the program did not have a sponsor. A sponsored broadcast would have had a commercial break a half-hour into the program. Welles also had longer intervals of music added to the broadcast to raise the suspense.

[in-text-ad-2]

10. Musical signature

The Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor, Opus 23, composed by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, was used as the theme to The Mercury Theatre on the Air program and opened the broadcast of “The War of the Worlds.” The concerto became associated with Welles throughout his career and was played when he was introduced on radio and television.

11. Not in real time

At the beginning of the broadcast, during Welles’ narration, he says, “In the 39th year of the 20th century came the great disillusionment. It was near the end of October. Business was better. The war scare was over. More men were back at work.” This was an indication that the show, broadcast in 1938, was not occurring in real time.

[in-text-ad]

12. Voice of authority

Included in the broadcast is a speech from the secretary of interior, who is never named. Welles was careful to choose this particular Cabinet post because it had less gravity than secretary of war or state, and it was done to appease CBS. The voice of the secretary, who describes efforts to combat the Martians, is that of Kenneth Delmar, an actor who did a spot-on Northeastern aristocratic accent that strongly suggested the voice of President Roosevelt. In 1938, the networks prohibited radio programs from impersonating the president so as not to mislead listeners.

13. Cops field calls

Apparently, the New Jersey State Police received enough phone calls about the “invasion” that it found it necessary during the program to send this teletype to police officers on duty: “Note to all receivers — broadcast as drama re this section being attacked by residents of Mars. Imaginary affair.”

14. The extent of the panic

How much of a panic was there? Probably not that much. According to Slate, a radio ratings service telephoned 5,000 households nationwide and asked, “To what program are you listening?” Only 2% indicated they were listening to a CBS program, where the play aired. This means that 98% of those surveyed were listening to something else or nothing at all at the time. That “something else” people were listening to might have been the “Chase and Sanborn Hour,” a comedy-variety show starring ventriloquist Edgar Bergen (Candice Bergen’s dad).

[in-text-ad-2]

15. Contrite Welles

At the press conference the day after the broadcast, Welles denied he had intended to deceive his audience. “I’m terribly shocked by the effect that it’s had,” he said. “Radio is new and we’re just starting to learn what effect it has on people. We are deeply shocked and deeply regretful about the results of last night’s broadcast.” Welles had an inkling of the impact the broadcast might have on the audience. At the close of the program, he stepped out of character and identified himself, saying “‘The War of The Worlds’ has no further significance than as the holiday offering it was intended to be. The Mercury Theatre’s own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying Boo!”

16. Sole-saving

One frightened listener tried to sue CBS for $50,000, claiming the network caused her “nervous shock” with the broadcast. Her lawsuit was dismissed. One claim was successful, however. A Massachusetts man sought compensation because he was saving money to buy a pair of shoes, and instead used the cash to buy a train ticket to flee the Martians. Welles reportedly agree to reimburse him for the shoes.

[in-text-ad]

17. The fuhrer weighs in on the furor

Adolf Hitler seized on the stories of panic in America following “The War of the Worlds” broadcast as an example of the decadence of democracies because they were so susceptible to a faux radio broadcast. “Nazi broadcasts said if American radio can lie about an invasion from Mars, then they can’t be trusted about anything they say about atrocities or Nazi aggression,” said Schwartz.

18. When Welles met Wells

Two years after the broadcast, Orson Welles met “The War of the Worlds” author H.G. Wells in San Antonio, Texas; they were each there by coincidence. They appeared together on a radio program, and the distinguished British science fiction writer was delighted to meet the American prodigy, calling him his “little namesake,” and characterizing the radio broadcast as a “sensational Halloween spree.” Wells also took the opportunity to ask Welles about his next project, which was a motion picture. Welles told Wells he was going to try some new cinematic techniques for his upcoming film, “Citizen Kane,” considered by many as the greatest film ever made.

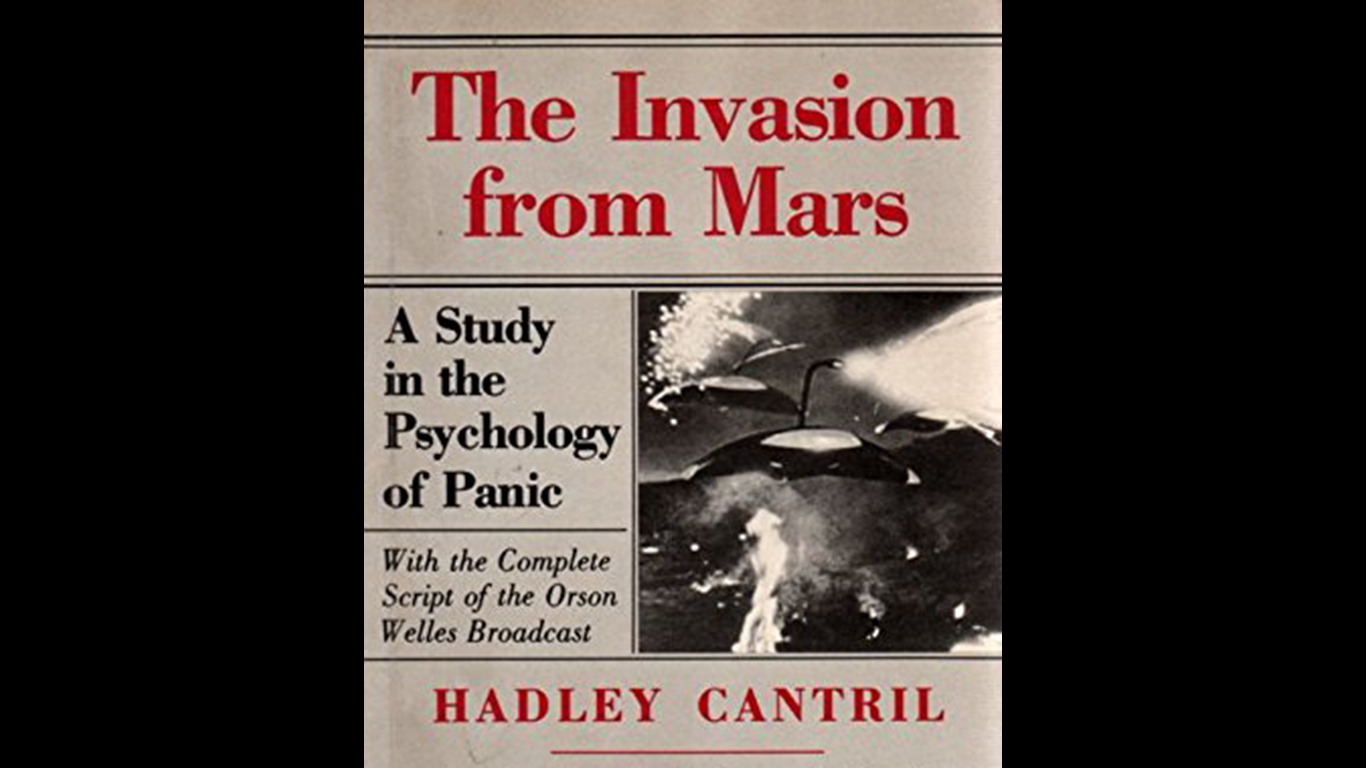

19. Analyzing the reaction

Days after the broadcast, social scientist Hadley Cantril embarked on research about the impact of the program and eventually published the study, “The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic.” It became the seminal research on the reaction to “The War of the Worlds” broadcast. For the first time, researchers had a significant data sample to measure reactions to a media event by various demographic categories. The study also showed how mass media can be used for propaganda purposes.

[in-text-ad-2]

20. Art imitating life

Frank Readick, the actor who played news reporter Carl Phillips on the broadcast, modeled his excitedly reported dispatches from Grover’s Mill on real-life radio reporter Herbert Morrison’s coverage of the Hindenburg disaster the previous year. That tragedy had occurred just 32 miles from Grover’s Mill, in Lakehurst, New Jersey. Readick became well known for his evil laughter that followed the introduction from “The Shadow” radio drama: “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!”

21. A productive career

John Houseman, producer of the broadcast, would enjoy a noteworthy career as producer of movies such as “Lust for Life” and “Executive Suite.” He would also do pre-production work for Welles on “Citizen Kane” and gain fame, and an Academy Award, for his portrayal of the imperious law professor Charles W. Kingsfield in the movie “The Paper Chase,” a role he would reprise on the television series by the same name. He died on Oct. 31, 1988, one day after the 50th anniversary of the broadcast.

[in-text-ad]

22. Here’s looking at you

Howard Koch wrote the script for the radio broadcast of “The War of the Worlds” and would go on to even greater acclaim for his collaboration with Julius J. and Phillip G. Epstein in writing the script for “Casablanca,” one of the most beloved movies of all time. In the 1950s, he was blacklisted by Hollywood for alleged communist associations, probably because he wrote the script for the World War II film “Mission to Moscow” that depicted America’s wartime Russian ally sympathetically.

23. A storied postscript

Three years after “The War of the Worlds,” Orson Welles, only 26 years old at the time, made what many film historians believe is the greatest movie of all time, “Citizen Kane.” He had a long, prolific career in motion pictures as an actor and director in films such as “The Stranger,” “The Third Man,” and “Touch of Evil.”

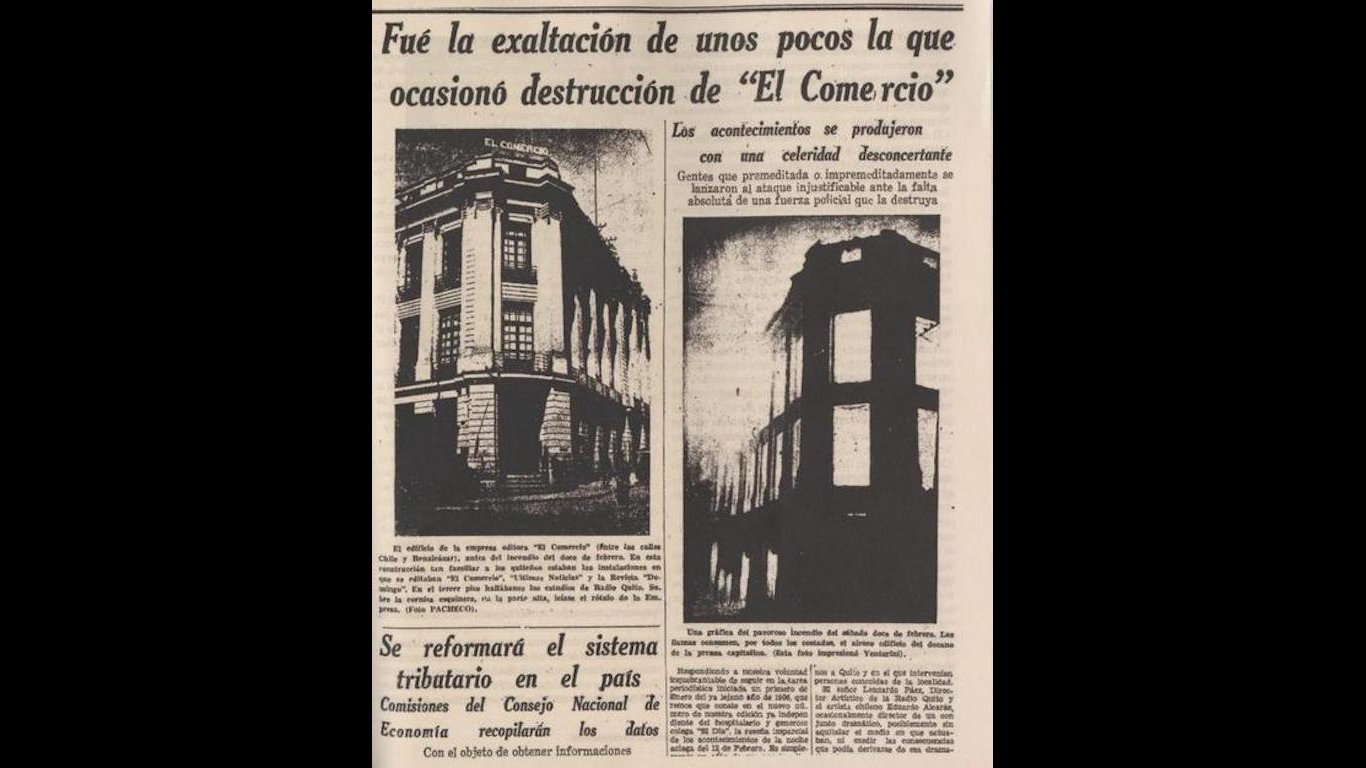

24. History repeats itself

“The War of the Worlds” broadcast has been reproduced many times, and in a few cases, it caused a panic. Radio stations in Buffalo and Ecuador did versions of the Orson Welles’ broadcast, changing the place names to local towns and areas. The reaction to the Buffalo broadcast in 1968 caused the Canadian military to send a force to the Peace Bridge that connects Canada and the United States. The reaction to the broadcast was deadlier in Ecuador in 1949 in the country’s capital of Quito. The military was sent to areas where the “Martians” had landed. Priests gave public absolutions to confessed adulterers. When people realized the invasion was a radio play, panic turned to anger. They attacked the radio station with rocks and set the building on fire. Some reports say six people died.

[in-text-ad-2]

25. Not so exceptional

Dorothy Thompson, a columnist for the New York Herald Tribune, said Orson Welles’ broadcast did the country a favor. “Far from blaming Mr. Orson Welles, he ought to be given a Congressional medal and a national prize for having made the most amazing and important contribution to the social sciences. For Mr. Orson Welles and his theater have made a greater contribution to an understanding of Hitlerism, Mussolinism, Stalinism, anti-Semitism and all other terrorisms of our times than all the words about them that have been written by reasonable men.” Letters sent to Welles concerning Americans’ reactions to the invasion echoed that concern, according to Schwartz. “One of the letters said, ‘If Americans are that gullible to this, America could go down the road to fascism as well,'” Schwartz said. “There had been this belief in American exceptionalism, that as democracies failed around the world, America would be different. For a lot of people, ‘War of the Worlds’ shattered that in that we could be misled just as easily.”

Detailed Findings

To understand how the panic could have occurred from the broadcast, one has to understand the world of 1938. And the world of 1938 was best understood through radio. By that year, the medium was no longer a novelty, but an essential part of American home life. The joke at the time was that people would rather default on a monthly car payment than give up their radio.

“It was the birth of mass communication, and people felt connected to events all around the world,” said A. Bradley Schwartz, author of “Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News.”

Radio combined intimacy and immediacy. The medium established its credibility with reports on the major news of the 1930s: the Lindbergh kidnapping, the exploits of gangsters like John Dillinger, and the explosion of the German zeppelin Hindenburg.

As tensions rose in Europe in the 1930s, American broadcasting companies sent teams of reporters to cover breaking news there. Radio distinguished itself with its coverage of the Munich summit involving Germany and the Western European democracies that for a time seemed to prevent war. By the fall 1938, listeners had grown accustomed to their radio programs being interrupted by news bulletins.

So when the soothing ballroom music played by Ramon Raquello and His Orchestra was interrupted by a news bulletin about explosions from Mars early on in the broadcast, it’s easy to understand how people who tuned in to the program and had not heard the disclaimer would have believed that what they were listening to was real.

We know now that the panic was not extensive. The show, broadcast over the Columbia Broadcasting System radio network, was opposite the top-rated program “The Chase and Sanborn Hour” that featured ventriloquist Edgar Bergen (Candice Bergen’s father) on the NBC radio channel, so its audience for “The War of the Worlds” was small. In his research about the incident, Schwartz said the panic was concentrated in areas where rumors can quickly spread, such as apartments and college dormitories.

Schwartz also said the reaction to the broadcast was varied. “Depending on when you tuned in, if you had not heard the reference to Martian invasion at the beginning of the program, and you heard invaders and war machines, some people might have thought it was a Nazi invasion,” he said. “The accounts of traffic around Grover’s Mill (where the Martians were supposed to have landed) were not because of people fleeing the scene but going to the scene. They had heard a meteor had landed and wanted to see what they could see.”

The next day, on Halloween, Welles met the press and was hammered with questions about the responsibility of radio. He came across as contrite and puzzled by the pandemonium his broadcast had caused. Even though “The War of the Worlds” would be described as a hoax or a prank, it was not intended as one by Welles. “It was a sore spot for him for a long time,” said Schwartz. “He had been hustled out of the studio by cops. He thought he could have been arrested at any moment and lose his liberty.”

In the aftermath of the furor, there was talk of how government should manage radio. Broadcasters met with the fledgling Federal Communications Commission, said Schwartz, and radio executives agreed not to use the terms like “news flash” and “bulletins” in dramatic programs.

“The War of the Worlds” broadcast left people skeptical about the veracity of news bulletins. When Pearl Harbor was attacked three years later, many people did not believe initial reports. “Reporters on the scene said this was real, this was not a play,” said Schwartz. “That was a lasting effect for a lot of people. Americans were forced to consider the downside of this new medium they had brought into their living rooms. It’s relevant today — how do we evaluate and think critically about what comes to us over the internet, social media, or on the radio? Those concerns remain front and center in any democratic society.”

Essential Tips for Investing: Sponsored

A financial advisor can help you understand the advantages and disadvantages of investment properties. Finding a qualified financial advisor doesn’t have to be hard. SmartAsset’s free tool matches you with up to three financial advisors who serve your area, and you can interview your advisor matches at no cost to decide which one is right for you. If you’re ready to find an advisor who can help you achieve your financial goals, get started now.

Investing in real estate can diversify your portfolio. But expanding your horizons may add additional costs. If you’re an investor looking to minimize expenses, consider checking out online brokerages. They often offer low investment fees, helping you maximize your profit.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.