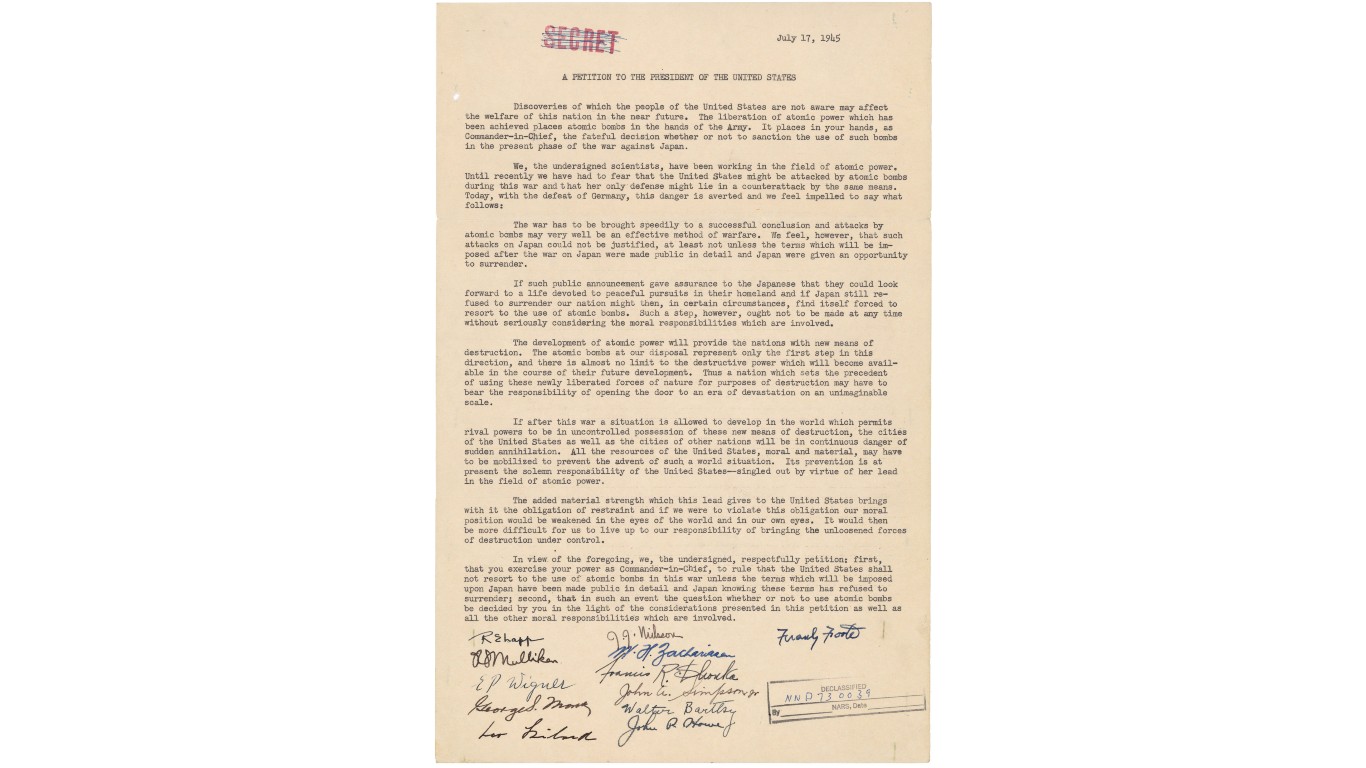

On July 17, 1945, a day after the U.S. tested the first atomic bomb, dozens of scientists involved with the Manhattan Project – which developed the world’s first nuclear weapons during World War II – signed a petition to President Truman written by their colleague Leo Szilárd, who had first proposed the idea of a nuclear chain reaction. The petition urged the president not to approve the use of atomic weapons without first offering Japan a chance to accept terms of surrender.

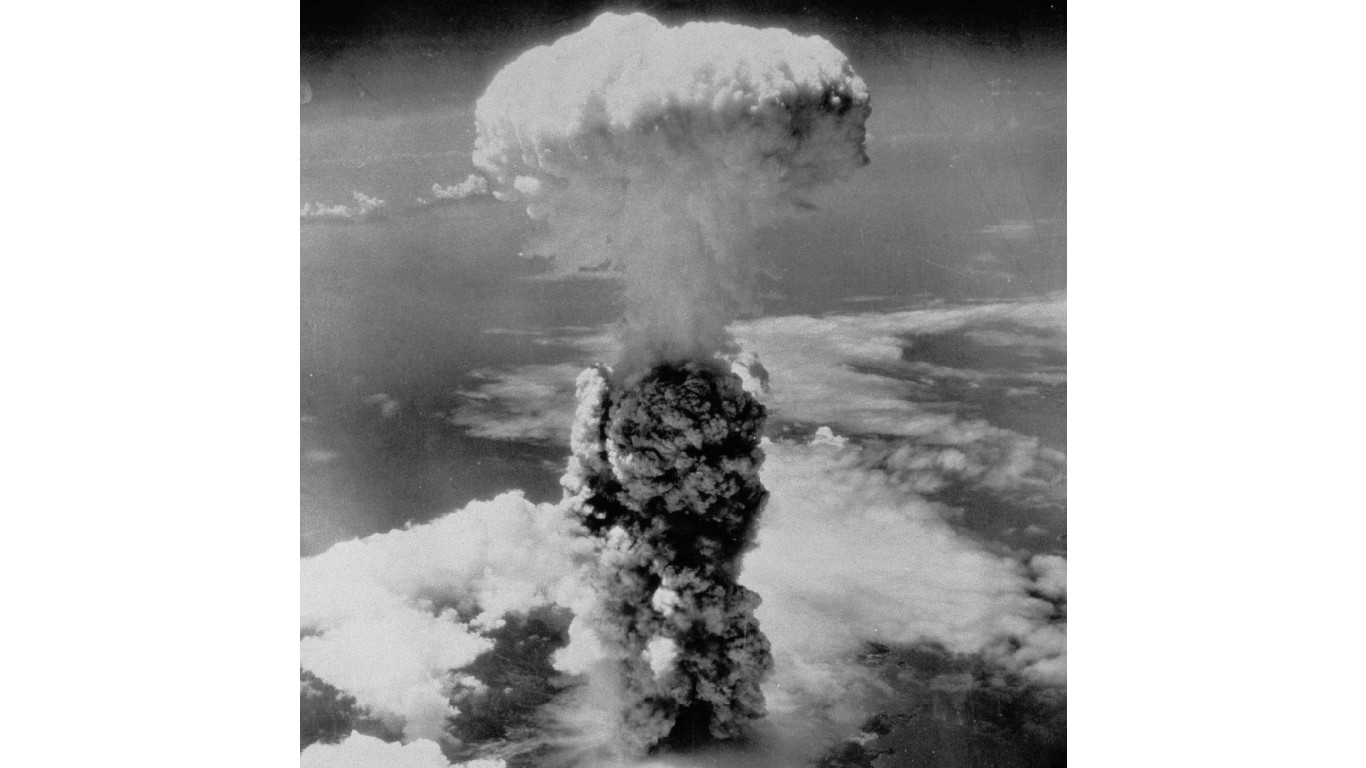

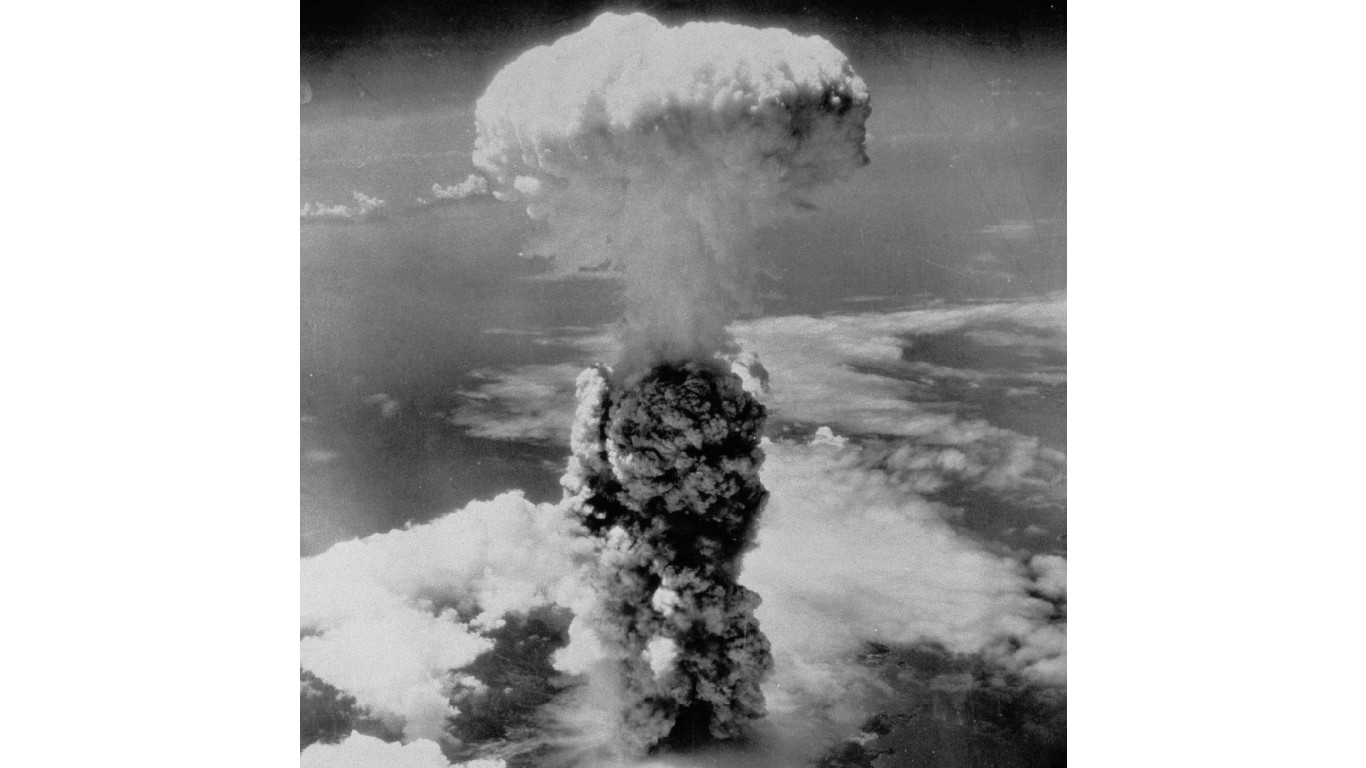

The scientists hoped that the U.S. might hold a demonstration for Japanese officials so that they could observe the effects of the bomb on an uninhabited area in order to avoid civilian casualties. Unfortunately, the president didn’t read the petition before the U.S. dropped the bombs on Japan, devastating the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (Read more about cities destroyed by the U.S. in World War II.)

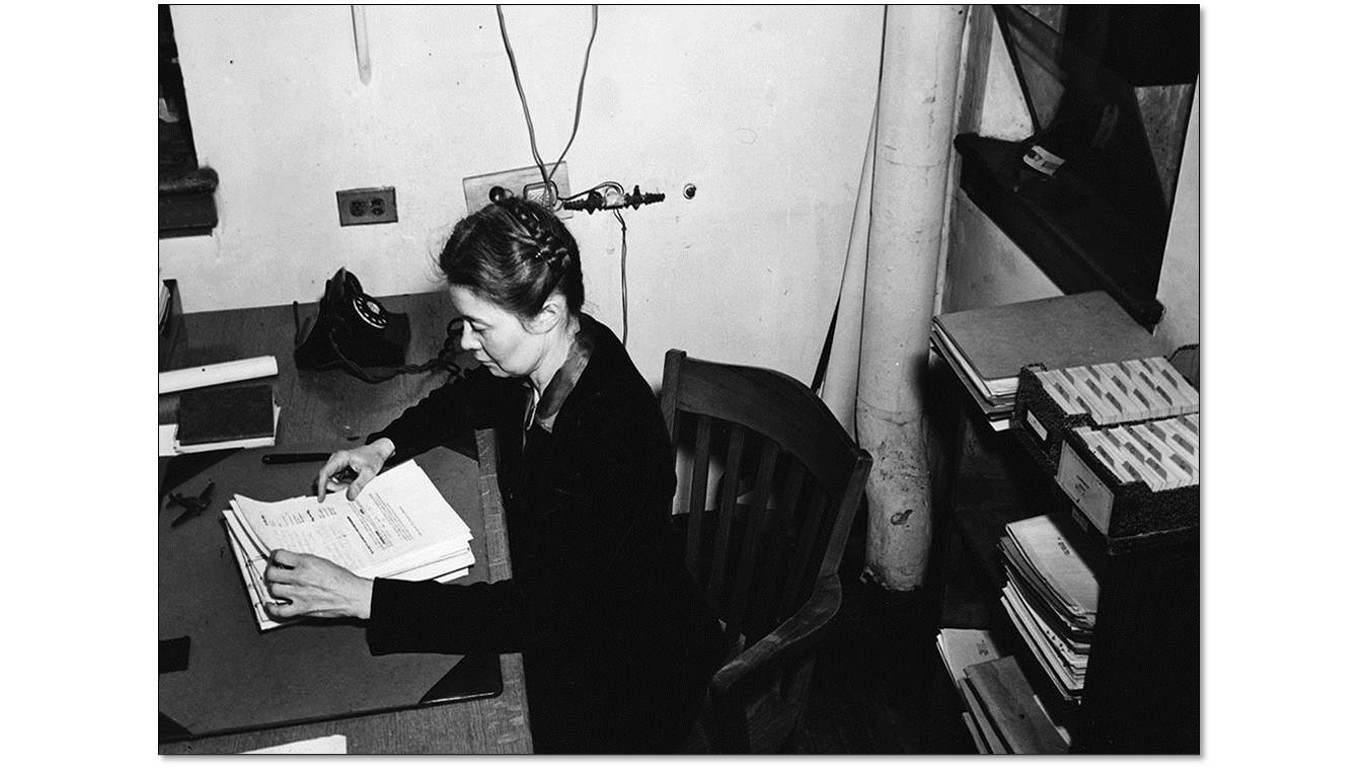

The Szilárd Petition, which was kept secret from the public and remained classified until 1961, was signed by over 70 scientists who had worked to create the bombs. Ten of these scientists were women. To determine the women scientists who worked on the atomic bomb and later opposed its use, 24/7 Tempo utilized information from the Atomic Heritage Foundation to generate a list of every woman who signed the petition.

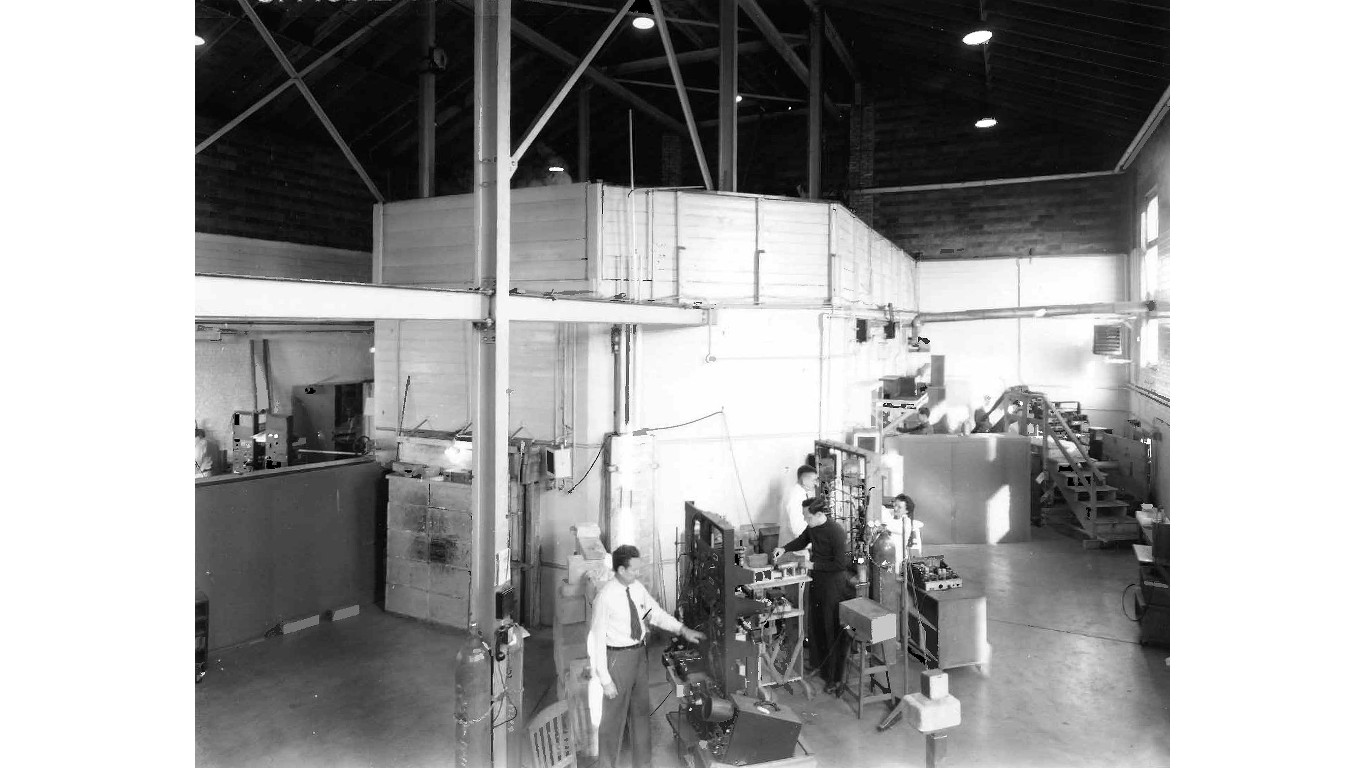

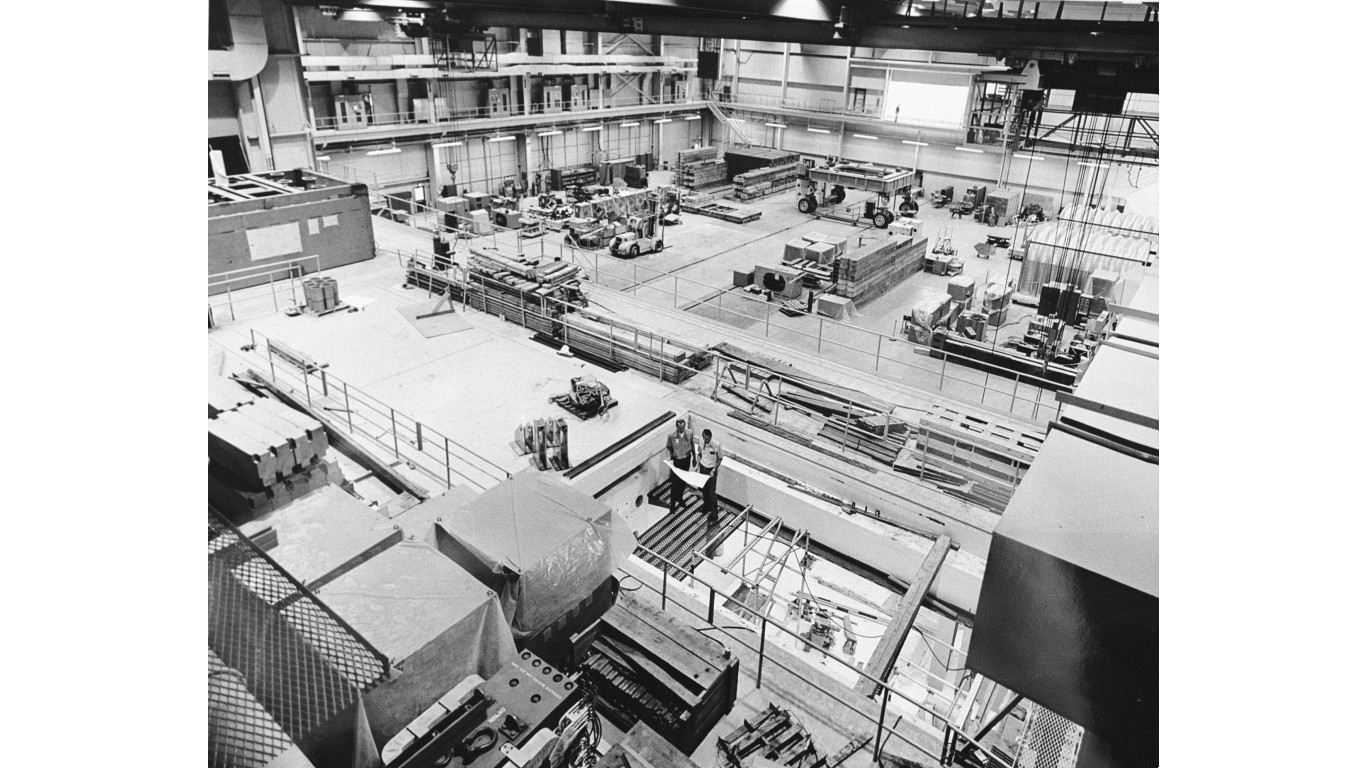

These women scientists who opposed the use of atomic weapons included two chemists, a psychologist, a biologist, a computer (meaning someone who did calculations), a technician, and four research assistants. All of them worked at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory, dedicated to the study of a newly discovered element, plutonium, and site of the first-ever artificial nuclear reactor.

Click here to read more about 10 women who helped develop the A-bomb, then opposed its use

After the war, one of the leading woman scientists on the Manhattan Project, Kay Way, went further to voice her opposition by compiling a book of essays called “One World or None: A Report to the Public on the Full Meaning of the Atomic Bomb.” Leading scientists including Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, and J. Robert Oppenheimer contributed essays to the book, which voiced concerns about the ethics of nuclear weapons. (The bombs dropped on Japan were some of the 18 deadliest weapons of all time.)

Mary Burke

> Position: Research assistant

Mary T. Burke served as a research assistant in the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago during the Manhattan Project, contributing to atomic bomb research in the Instruments Division.

[in-text-ad]

Ethaline Hartge Cortelyou

> Position: Junior chemist

Ethaline Hartge Cortelyou got her bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Alfred College in 1932. As a junior chemist at the Met Lab during the Manhattan Project, she assisted in preparing the classified table of isotopes. In her later years, she continued scientific writing and was a strong advocate for women in STEM.

Mary M. Dailey

> Position: Research assistant

Mary M. Dailey was a research assistant in the health division at the University of Chicago’s Met Lab during the Manhattan Project.

Miriam Posner Finkel

> Position: Associate biologist

Miriam P. Finkel, an associate biologist at the Metallurgical Laboratory during the Manhattan Project, researched the toxicity levels of radionuclides and the effects of radiation exposure. She received her B.S. in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1938, and her Ph.D. in 1944. Finkel’s research helped develop health and safety standards for radiation exposure and contributed significantly to molecular biology.

[in-text-ad-2]

Mildred C. Ginsberg

> Position: Computer

Mildred C. Ginsberg Goldberger was an American mathematician and economist who served as a research assistant and computer (meaning someone who calculates) at the Met Lab. She received her B.A. in mathematics from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and later served as the First Lady of CalTech.

Marietta Catherine Moore

> Position: Technician

Marietta Catherine Moore served as a technician in the health division at the University of Chicago’s Met Lab during the Manhattan Project.

[in-text-ad]

Margaret H. Rand

> Position: Research assistant

Margaret H. Rand was another research assistant in the Met Lab’s health division during the Manhattan Project.

Marguerite N. Swift

> Position: Associate physiologist

Marguerite N. Swift served as a Manhattan Project associate physiologist in the health division at the University of Chicago’s Met Lab.

Katharine Way

> Position: Research assistant

Katharine “Kay” Way was one of the Manhattan Project’s leading women scientists. She obtained her bachelor’s in physics from Columbia University and then completed her PhD in nuclear physics. At the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, she helped develop the Way-Wigner formula for calculating nuclear fission product decay, and her expertise in the area brought her to other project sites including Hanford, Los Alamos, and Oak Ridge.

[in-text-ad-2]

Hoylande Young

> Position: Senior chemist

Hoylande Young was educated at Ohio State University and the University of Chicago, earning a Ph.D. in organic chemistry. While working as a senior chemist at the Met Lab, she also served as an editor of the National Nuclear Energy Series, a wartime report on nuclear research. She later became the Director of Technical Information at Argonne National Laboratory.

Want to Retire Early? Start Here (Sponsor)

Want retirement to come a few years earlier than you’d planned? Or are you ready to retire now, but want an extra set of eyes on your finances?

Now you can speak with up to 3 financial experts in your area for FREE. By simply clicking here you can begin to match with financial professionals who can help you build your plan to retire early. And the best part? The first conversation with them is free.

Click here to match with up to 3 financial pros who would be excited to help you make financial decisions.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.